The Prabowo Campaign's 'Cute Aggression'

Or how I was wrong about the risk of AI in the 2024 Indonesian elections.

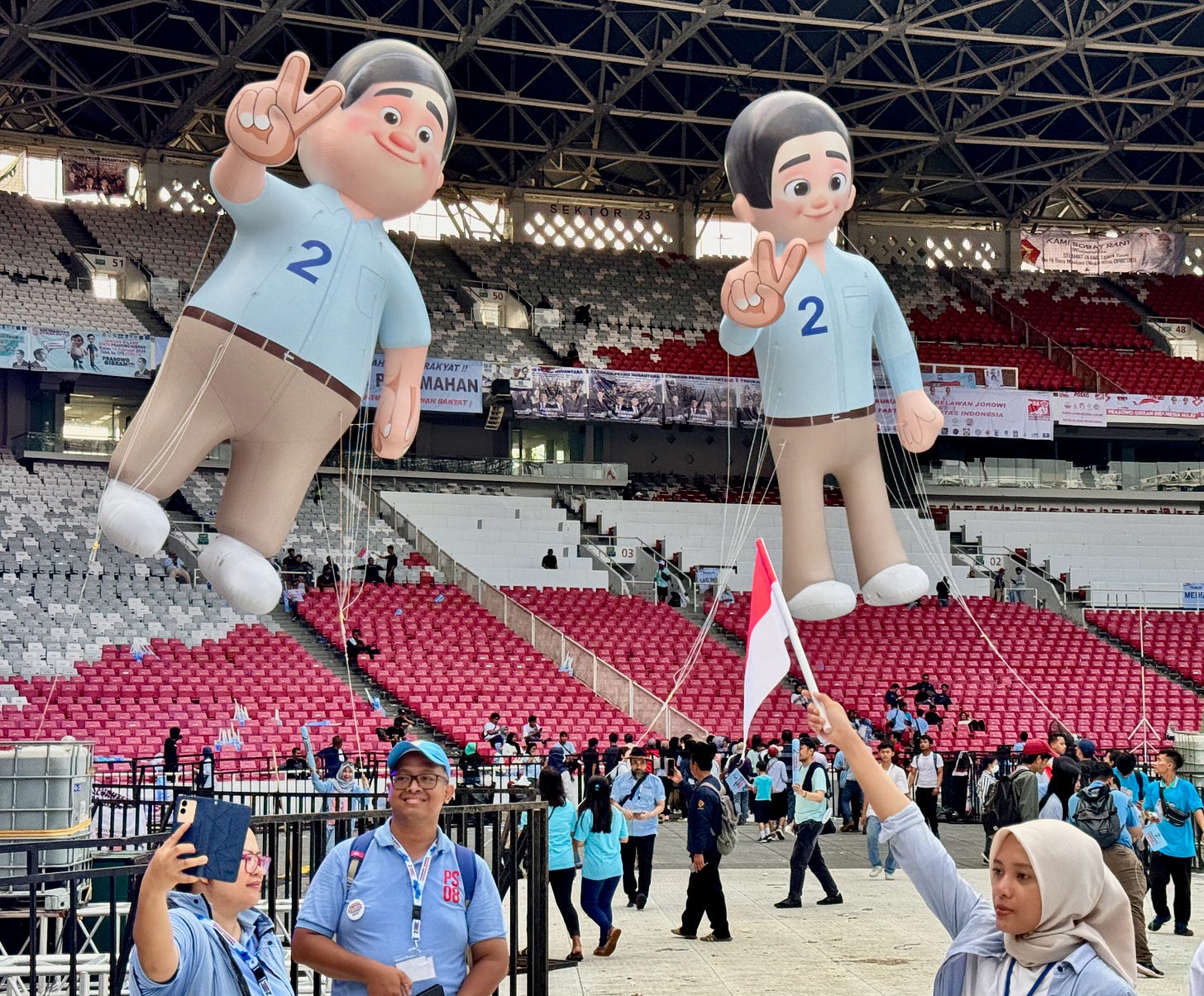

Foreign journalists covering Prabowo Subianto’s overwhelming February 14 victory in Indonesia’s presidential election have struggled to translate the Indonesian concept that was central to the effort to re-brand the former general and Suharto son-in-law as an innocuous elder statesman. The concept has been called “cute”, “cuddly”, “adorable”, and it was the theme for campaign t-shirts, billboards, and giant inflatable mascots. But none of the translations were quite right.

That’s because gemoy, the Indonesian concept used by the Prabowo campaign, is youth slang for gemas—a word with no English equivalent. That the concept exists in Indonesian (and some other languages) but not in English tells us something interesting about the power of Prabowo’s re-branding.

Gemas is the Indonesian word for what in 2015 the social psychologist Oriana Aragón termed “cute aggression”. This is the feeling of being overwhelmed by cuteness that can cause someone to, for instance, want to pinch the cheeks of a child. Notice that the term refers not to the cute object itself but to the emotion when perceiving cuteness. Gemas is not even captured by the well-known Japanese word for cute, kawaii, which is something else again.

According to Aragón, however, cute aggression is a universal human emotion even if a word for it exists only in certain languages. In Tagalog it’s gigil. She theorizes that the contradictory emotions might have converged evolutionarily for the purpose of emotional regulation—a kind of cuteness circuit breaker.

According to the Prabowo campaign the gemoy motif emerged organically from social media. Speaking on the origins of the term, Prabowo campaign spokesperson Cheryl Anelia Tanzil denied it had been created by the team as part of a strategy. Likening it to another popular youth slang term, santuy (“relaxed”), Tanzil explained to Indonesian media that “the terms gemoy and santuy are an oasis for voters who now see that politics can be made cool and happy.”

Another Prabowo spokesperson, Rahayu Saraswati Djojohadikusumo, who is also the candidate’s niece, further explained that once the term stuck the national campaign team was happy to adopt it as a way to attract millennial and Gen Z voters. And it seems to have worked. According to a Quick Count by Litbang Kompas, Prabowo-Gibran won 65.9% of the Gen Z vote, or voters under 26—their most successful demographic.

The primary cause of the Prabowo landslide was support by outgoing president Jokowi, who had his son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, join the Prabowo ticket as candidate for vice president. This move made Prabowo the choice for voters seeking a continuation of the Jokowi era’s relative stability and economic growth. But to be the continuity candidate Prabowo had to match an electoral mood averse to radicalism and risk. The Prabowo brand of 2014 (militant nationalist) and 2019 (Islamist) had to be replaced by something. Into this void gemoy was the perfect fit.

Gemoy also served to balance Prabowo’s traditional image among Indonesian voters as tegas (“firm”), itself an Indonesian concept with no easy English equivalent as it connotes both decisiveness of action and clarity of thought. Tegas remains at the core of Prabowo’s charismatic authority among older generations. But gemoy helped to take the edge off Prabowo’s image in concert with a campaign narrative that there was nothing to fear in electing the former military hardliner, ostensibly now a changed man.

On the streets of Jakarta, gemoy was the principle behind the cartoon “AI imagery” of Prabowo and Gibran, staring down from numerous billboards wide-eyed, chubby-cheeked, and de-aged. But the more important AI might have been the social media algorithms that “discovered” cute aggression optimizes user engagement with Prabowo-Gibran content.

This is campaign design without a designer. But because Indonesian has a concept for the emotion the official campaign could easily adopt and redeploy it in a strategic way that would not have been possible in an English-language context. This appears to have happened rapidly in the final months of the campaign. In December, volunteers were encouraged to share their own AI-generated gemoy images via an official campaign volunteer site, prabowogibran.ai. The proliferation of different variants of the gemoy meme across even official media is evidence of a lack of top-down design.

By the end of the election campaign in February, multiple AI versions of Prabowo and Gibran were suddenly everywhere. Whereas in 2014 Prabowo, a keris (dagger) on his waist, had ridden into his campaign finale at Gelora Bung Karno stadium on a white horse, invoking the 19th century Javanese warrior-prince Diponegoro, in 2024 he danced on stage in a baby-blue shirt to match the stadium-high inflatable cartoon figures and giant digital avatars that bobbed and floated above the masses.

Why did gemoy rise from social media to such political heights? On the internet heightened emotional affect fuels the “attention economy”. Outrage drives clicks, cats dominate memes, and the laughing-crying face is the most popular emoji. Likewise, gemoy flooded social media feeds with cuteness. Bright rounded shapes and soft kindchenschema smoothed over human rights concerns long-attached to the image of Prabowo.

In 2019, after OpenAI released its breakthrough GPT3 large language model, I wrote for Lowy Interpreter about what I anticipated would be an “unintelligence explosion” of AI-generated disinformation. I thought the flood of automated disinformation would be the most significant impact of the AI revolution long before any so-called “intelligence explosion” creates existential risk to humans from superintelligent agents.

It’s early days in generative AI but disinformation hardly played a role in the 2024 Indonesian elections. Instead, we saw a kind of mixed reality campaign in which a virtual layer was used to make the intangible tangible. Jokowi’s popular infrastructure projects—trains and roads—are tangible. The capital city under construction in Borneo—centrepiece of the Jokowi legacy—exists in the metaverse. And during the Prabowo campaign, gemoy—in a TikTok dance or a photo booth—was real.